How I Product Manage Imposter Syndrome

Four things I did to manage my imposter syndrome

I had a bad case of imposter syndrome as a product manager. I’m going to tell you why product managers have the highest rates of imposter syndrome ever, how I product managed my own imposter syndrome to be able to work faster and happier – in a state of flow, like a machine, a happy machine – and then I’ll summarize all of the research and success stories we could find to show exactly how to beat this imposter phenomenon.

We’re all imposters

About 70% of people, in general, will suffer from imposter syndrome at some point. (Source: PubMed)

And the percentage tends to go up as skills and pressure increase; for example, the highest levels found in a recent meta-study, a study of studies, showed that 82% of Austrian doctoral students experienced at least low levels of imposter syndrome at some point. (Source: meta-study)

Step aside Austrian doctors because a whopping 92% of product managers have felt imposter syndrome at some point. This is according to a survey conducted by ProductPlan, of 2,200 product managers in 2021.

You might be thinking, oh my gosh, only 8% of product managers are stable? No, I would say this tiny group, if they’re doing anything innovative, is possibly delusional; I’ll let Seth Godin explain…

“Of course, you feel that way because you are an imposter, and so am I. Because if you are doing work that hasn't been done before, which means creativity or leadership, then you can't be sure it's going to work because it's never been done before.”

– Seth Godin (Source: North Star Podcast @ 06:35)

Even the most brilliant people suffer from imposter syndrome because they’re doing something that’s never been done before.

Einstein called himself an “involuntary swindler” because people thought he knew everything when he didn’t. For example, he didn’t believe in black holes, exhibit A, or quantum mechanics, exhibit B. (Sources: The New Yorker, History, Nature)

We often look at product leaders the same way, believing they know everything when they don’t.

The image below was version 1 of Twitch, the service that invented a new social gaming industry.

It was just one web page, streaming a guy named Justin 24/7. Mistakes, learning, and iterations are part of the product development process, but we just see the success at the end without asking, “Hey, Justin, did you know everything all the time? Did you ever have imposter syndrome?”

“The answer is yes, I absolutely have, and you'll be surprised because I felt it even after selling Twitch for a billion dollars… Recognize that everybody else has imposter syndrome all the time also.”

– Justin Kan, Twitch founder (Source: YouTube @ 00:09 and @ 04:11)

Justin Kan, and researchers at Cleveland Clinic, suggest you stop comparing yourself to other people, for starters, because you’re only seeing a tiny snapshot, a single Instagram post, of success without asking if there were doubts and mistakes along the way. (Source: Cleveland Clinic)

The Cleveland Clinic article reminds us that smart, high-achieving people often deal with imposter syndrome. So, simply having these thoughts puts you in good company, and true imposters don’t have these thoughts… I’m talking about you, Sam Bankman Fried and Elizabeth Holmes, and anyone else on the cover of Forbes to whom I shouldn’t compare myself.

Product managers are imposters

But why do 92% of product managers feel like imposters? It’s the same reason why 90% of startups completely fail (source: Startup Genome, 2022 report). It’s the same reason 95% of new products fail (source: Inc. Magazine) — allegedly, the true stat would be impossible to know as many products die before they hit the market and even successful products have a shelf life, just like blackberries or the BlackBerry phone.

The point is launching successful products is hard. Even if you’re part of the small percentage that succeeds, you still have to fake it until you make it because “you can't be sure it's going to work because it's never been done before.” Despite the overwhelming failure rate and uncertainties, for unknown reasons, entire teams of people believe in us to lead a product to success.

You might not be facing a colossal product failure that ends up on the front page of TechCrunch, but even day-to-day failures can be imposter-syndrome-inducing. Maybe users aren’t adopting your new feature as quickly as you predicted, or your latest launch failed to improve an important KPI. Even when you do everything by the book, you’ve done your discovery, you’ve surveyed the market, you’ve talked to customers, things can still go sideways. Product development is hard, and we all face failures, learnings, and challenges. But as Marty Cagan points out in his book Inspired:

“When a product succeeds, it’s because everyone on the team did what they needed to do. But when a product fails, it’s the product manager’s fault.”

– Marty Cagan (Source: Inspired, chapter 10)

The responsibility and accountability that we PMs hold on our shoulders are enormous.

An imposter is a person who pretends to be someone else. Saaayyy a product manager who acts like they know everything about launching a successful product. As product managers, we have to know a lot about a lot of things, but it’s impossible to be skilled in all the disciplines needed to launch a successful product. It takes a village of specialists–engineers, designers, product marketers, data scientists, and on and on–and we’re supposed to lead them all despite not being specialists ourselves.

A product manager neither has the expertise of everyone building the product nor is an actual manager. Product managers usually don’t have authority over the teams they lead, which is why I have an entire course on this, called Product Influence, available now.

It’s right there in the name “product manager,” but if we are not managers, does that make us imposters? At least 92% of us feel that way. And what is that feeling exactly? Well, I’ll let Tom Hanks explain it…

“No matter who we are, no matter what we've done, there comes a point where you think, how did I get here, and am I going to be able to continue this? When are they going to discover that I am, in fact, a fraud and take everything away from me?”

– Tom Hanks (Source: NPR interview @ 03:50)

Imposter syndrome is that terrible feeling: I’m a fraud, and they're going to catch me.

I’m an imposter

I’ve always had a little imposter syndrome in the back of my head, but it became a real problem when I was promoted to Senior Product Manager. The problem with success, well, I’ll let Neil Gaiman explain it:

“The problems of success can be harder because nobody warns you about them. The first problem of any kind of even limited success is the unshakable conviction that you're getting away with something and at any moment now, they will discover you. It's imposter syndrome.”

Ironically, the more you succeed, the more you see how much you don’t know, and the more other people believe you do know. That’s when you start to think, I should know all this stuff people think I know.

Before being promoted to senior PM, I was on top of the world. I was good at my job, and I was full of confidence. I moved to a new company and took on a bigger title; I became a Senior Product Manager. And that’s when the trouble started. I went from being a confident product manager who knew all the ins and outs of a rocketship marketplace startup to suddenly being a senior product manager at an enterprise SaaS company with a highly complex data product. It was a product, an industry, and a business model that I knew nothing about. But I was a senior PM, so I was supposed to know everything, right?

Almost overnight, my confidence vanished. I went from believing I was a great product manager to thinking, “I don’t even understand the basics of this entire industry or how this product works, let alone how to manage it. I’m a fraud, and they’re going to find me out.”

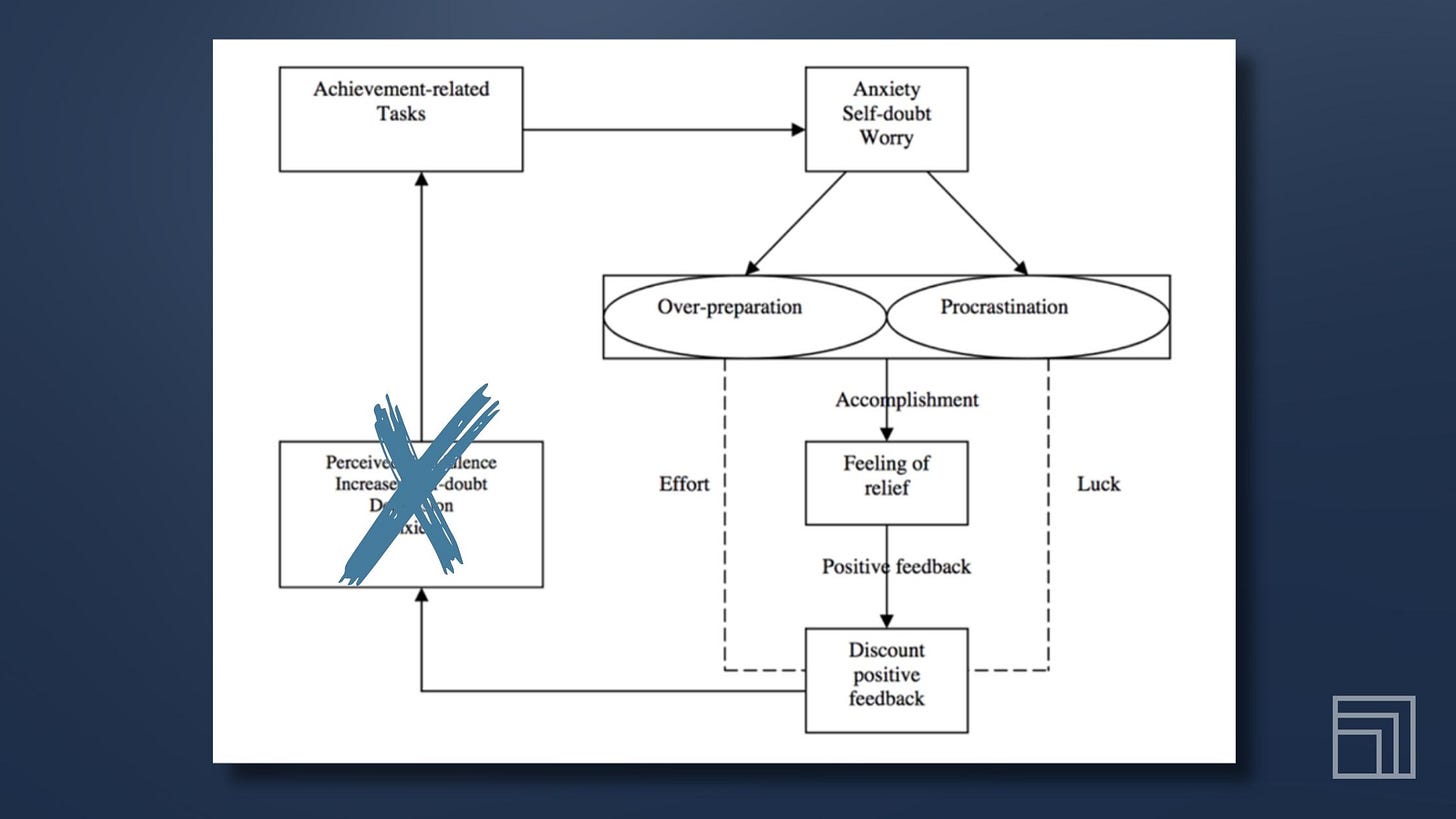

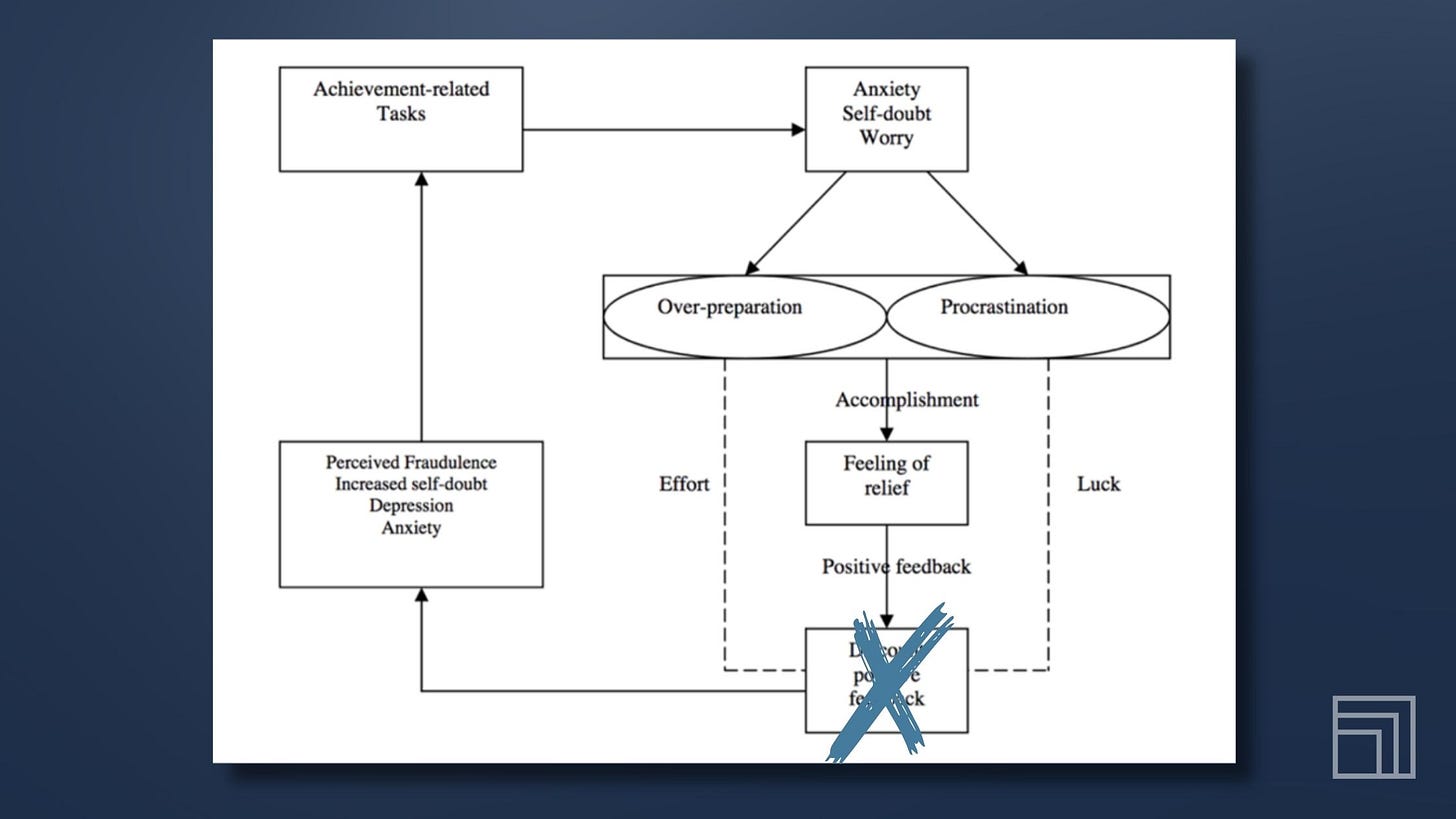

The imposter cycle

That’s part of the imposter cycle. You achieve so much, but then you discount those achievements and instead think, well, I worked so hard on that, and you chalk the success up to the effort, or worse, you chalk it up to luck. You forget or ignore that your capabilities got you to this place of success. (Source: APA)

I was so stuck in the imposter cycle that I ignored that I had five years of product management under my belt, that I was good at working with engineers and stakeholders, and that I could connect with customers and be strategic. I ignored my capabilities. My achievements were meaningless. My imposter syndrome told me I was just a lucky workaholic.

The problem with product management is that a lot of it is luck, because most products and their managers fail, 95% fail, allegedly. I just happened to work for unicorn startups. What if I don’t get that lucky again next time, Tom Hanks?

“And if I can't do it, that means I'm going to have to fake it. And if I fake it, that means they may catch me at faking it. And if they catch me at faking it - well, then it's just doomsday."

– Tom Hanks again (Source: NPR interview @ 04:15)

F#%!ing doomsday. When I started at that complex enterprise SaaS company, I felt like doomsday was knocking at my door, and I had this paralyzing mental fog that destroyed my ability to think. I couldn’t get into a state of flow. And that’s when it all changed for my imposter syndrome.

Product managing my imposter syndrome

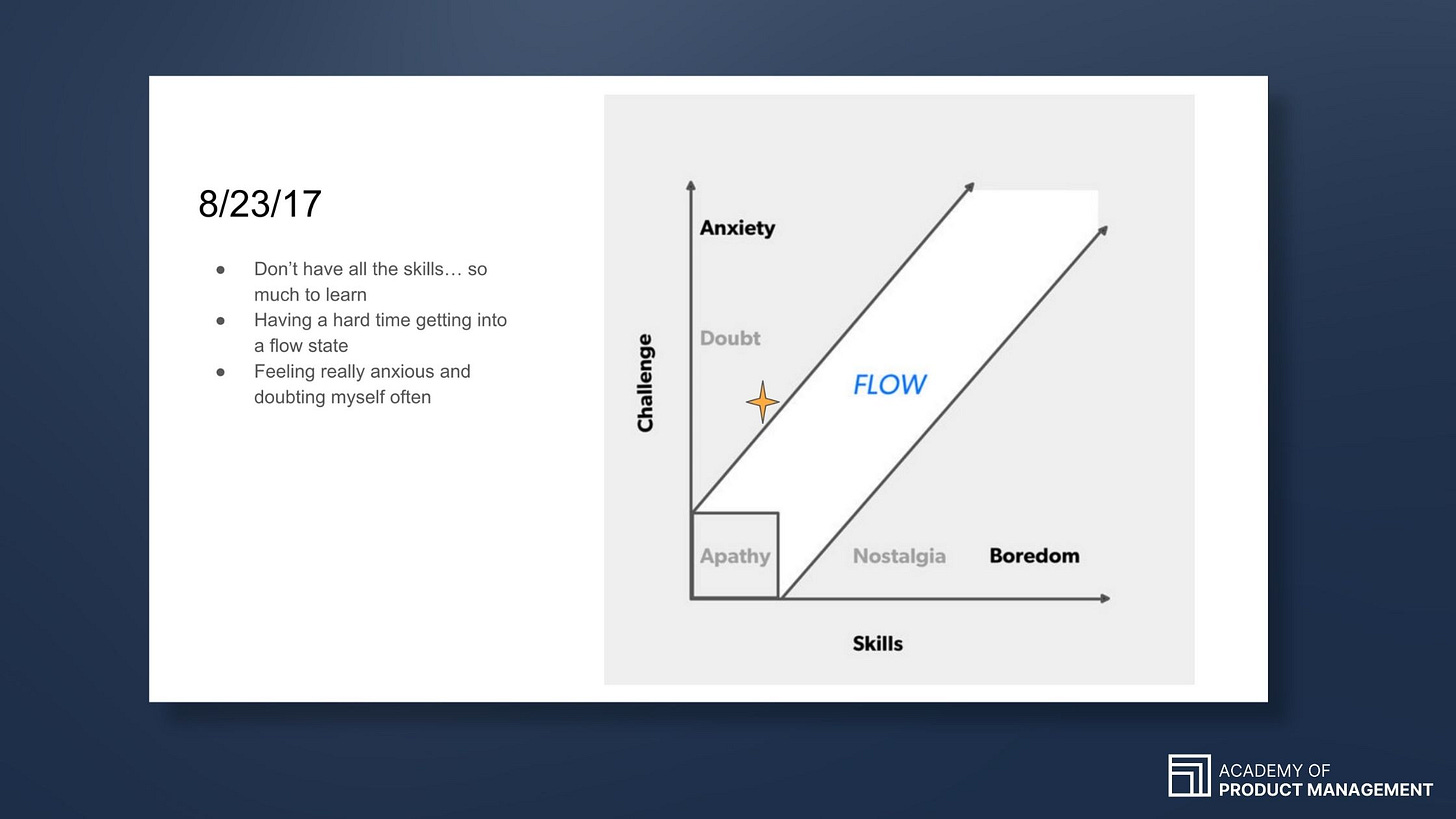

During this time, I stumbled upon this First Round Review article about a framework used by engineering leader Cynthia Maxwell to track her direct reports’ flow states. Using a simple chart, she’d ask the individual, ‘How do you feel about the work that you're doing right now?’ and have them plot it on the chart. This helped Maxwell measure flow states for her teams of engineers and allowed her to recognize when people were out of flow due to boredom when their skill level was greater than their assigned tasks or due to self-doubt when the challenge was greater than their skill level.

As a data nerd and productivity junkie, I was intrigued by this approach and decided to plot my own emotional state. Here’s how I scored; literally, this is a screenshot of the chart I plotted back in 2017, less than 90 days into the job. I realized I was anxious and doubting myself; the worst my imposter syndrome has ever been, simply because I didn’t have some of the skills I needed to do my new job.

Seeing it plotted on a chart like this made it obvious what I needed to do to get out of the doubt region. To get back into flow (a state of confidence and content), I would need to increase my skills – that was something I could control.

Step 1: Make a roadmap to learn what you don’t know.

I created a list of things I needed to learn to feel comfortable in the day-to-day job (e.g., parts of the tech stack, specific customer problems, and industry trends I needed to understand more deeply). I made a spreadsheet to track what I wanted to learn and blocked time on Friday afternoons to study. I kept track of what I was learning and added to the list whenever I encountered a new topic that I felt unsure about. I lovingly called the list my “‘WTF is this?’ list.”

Less than one month later, my anxiety had significantly improved. (Yes, this screenshot is real!) My imposter syndrome wasn’t fixed yet, but simply charting what I knew and what I didn’t and showing my progress was enough to get me back to flow, or at least basic brain function.

I had product managed my imposter syndrome! Like a good product manager, I had defined…

A north star metric/outcome → Increased time in a flow state.

A strategy to achieve that outcome → Identify gaps in my knowledge holding me back from flow and learn those things.

And a roadmap → I prioritized the topics on my “‘WTF is this?’ list” and completed at least one topic each week.

My learning plan was my roadmap, my strategy was spot on, and I nailed that OKR.

I used this approach again a few years later when I was promoted to a platform product manager role. The new role had me leading Product for six teams with roughly 30 engineers, focused on complex technical areas I knew nothing about. By using this method up front, I avoided the crippling imposter syndrome I had experienced before, even though the challenge was far beyond my skill set.

Why did this work? Looking back, my “‘WTF is this?’ list” helped me reframe my knowledge gaps as opportunities. Because the title was funny, looking at the long list of stuff I didn’t know evoked a feeling of curiosity (🤔“Huh, wtf is that?”) instead of shame (😰“OMG, I should know this, but I don’t. I’m a fraud!”), and treating my learning like a roadmap helped me avoid overwhelm. I didn’t have to know everything because I had a prioritized study plan for how and when to learn it. (Get the template to create your own study plan here.)

The research shows deeper reasons why my approach worked: Imposter syndrome is rooted in discounting your accomplishments, which is hard to do when you’re literally checking off a list of accomplishments (things you’ve learned) and making progress. Funny enough, Cynthia Maxwell used these charts to measure flow because she wanted to improve job satisfaction and reduce burnout rates after a talented engineer quit her team.

Those are the same negative effects that result from imposter syndrome. The first thing research recommends is to recognize those feelings and address them with career development training if they have merit (source: meta-study). If you fear people will find out you don’t know something, well, go and know that something, and most importantly, track and acknowledge your progress.

Step 2: Share how you’re feeling with trusted colleagues to get feedback.

Focusing on learning what I didn’t know helped rebuild some of my confidence, but it didn’t rid me of my imposter syndrome completely. I also started to open up about how I felt, step 2. The first person I talked to was my manager. I told him about my learning plan (though I didn’t tell him I called it the “‘WTF is this?’ list”… ) and was relieved that he was supportive, not appalled.

As my confidence grew, I began to open up about my imposter syndrome to other product managers on my team who I trusted, which sparked a lightbulb moment. I’ll let Atlassian co-founder Mike Cannon-Brookes explain…

“I remember admitting to him that I felt that we did not deserve to be there, that we were well out of our depth and at some time, someone was going to figure this out and send us home to Australia. And he, I remember, just paused and looked at me and said that he felt exactly the same way and that he suspected all the winners were feeling that way and that despite not knowing Scott [or I] or really anything about technology, he said that we were obviously doing something right and should probably just keep going.”

– Mike Cannon-Brookes, Atlassian co-founder (Source: YouTube @ 06:24)

Lightbulb moments like his are recounted by people overcoming imposter syndrome over and over again. This is step 2, according to the APA, to share your feelings (source: APA). You can’t be an imposter if you stop posturing as if you always know what you're doing. Talking about your feelings stops the cycle, because you can no longer fear they’ll find you out if you just told them.

In product management, getting feedback is critical to know if your product is on the right track. It’s the same approach for imposter syndrome. Feedback will let you know if your negative thoughts have merit and help you address those needed skills. But, you’ll probably learn that your thoughts are irrational, and that you’re not alone.

Realizing that most people are going through the same thing is a lightbulb moment because you think to yourself, maybe these feelings don’t mean I’m an imposter because this other person has these feelings too, and they're not an imposter; they're great, so maybe we can both just keep going.

I later joined a high-achieving professional women’s group, where many members, like me, struggled with perfectionism and imposter syndrome. Being part of this group was amazing. Part of imposter syndrome treatment is to treat yourself as kindly as you would a friend. And when you’re telling your high-achieving friends they're being totally ridiculous, you realize you are too, and it stops the cycle. The imposter feeling is irrational, and you just need to remind yourself of that.

Step 3: Remind yourself what you’re capable of.

And that’s step 3. I call it “Repeat, Repeat, Repeat” in my product management courses; say the same thing over and over so your audience doesn’t forget it. Well, this time you’re the audience, and you need to remember that you got this.

I journal every day. I write down my irrational fears (usually prompted by the question, “What scares me today?”) and then I write down my capabilities and achievements that counteract those thoughts. I remind myself that I am happy to be at work and it’s my choice to do the work I do.

And I ask myself, “What’s the worst that could happen?” The product fails like 95% of products? Well, that’ll be a great story, I’ll learn a lot along the way, and I’ll try again. The things that scare us are usually not as scary as our minds make them.

Step 4: Celebrate your accomplishments.

The fourth and final step is the best advice Neil Gaiman ever received…

“I was writing a comic people loved, and they were taking it seriously, and Stephen King liked Sandman and my novel with Terry Pratchett Good Omens and [he] saw the madness that was going on, the long signing lines, all of that stuff and his advice to me was this, he said, ‘This is really great. You should enjoy it.’ And I didn't. Best advice I ever got that I ignored.”

– Neil Gaiman (Source: YouTube @ 15:28)

This last piece is crucial. When you have an accomplishment, instead of flying past the feeling of relief and positive feedback, instead of discounting it to effort or luck, just stop and enjoy it.

Celebrate your success. Write it down and celebrate it again later (source: APA). Acknowledge that it wasn’t just luck or over-working that got you there; no, you did that.

And that’s it. I use those four steps to manage my imposter syndrome as a product manager.

1) Make a roadmap to learn what you don’t know.

2) Share how you’re feeling with trusted colleagues to get feedback.

3) Remind yourself what you’re capable of.

And 4) Celebrate your accomplishments.

This job is hard. Remember that we all feel like imposters sometimes, but you got this.

Resources

Here’s a summary of the resources mentioned in this post, to help you manage your own imposter syndrome.

Track and Facilitate Your Engineers’ Flow States In This Simple Way | First Round Review → Explains how to track your flow state

References:

[meta-study] Prevalence, Predictors, and Treatment of Impostor Syndrome: a Systematic Review - PMC (PubMed)

The State of Product Management Report in 2021 | ProductPlan

Seth Godin: Writing Every Day - David Perell (North Star Podcast)

Even Albert Einstein Had His Doubts About Black Holes (History.com)

Did Einstein really say that? (Nature.com)

Twitch Co-Founder Had Imposter Syndrome...Even After Selling Twitch (Justin Kan, YouTube)

Impostor Syndrome: What It Is and How To Overcome It (Cleveland Clinic)

The State of the Global Startup Economy (Startup Genome)

95 Percent of New Products Fail. Here Are 6 Steps to Make Sure Yours Don't | Inc.com

Inspired by Marty Cagan

Tom Hanks Says Self-Doubt Is 'A High-Wire Act That We All Walk' : NPR

Neil Gaiman Addresses the University of the Arts Class of 2012 (The University of the Arts, YouTube)

Track and Facilitate Your Engineers’ Flow States In This Simple Way | First Round Review

Imposter Syndrome | Mike Cannon-Brookes | TEDxSydney (TEDx Talks, YouTube)

How to overcome impostor phenomenon (APA, American Psychological Association)

Those 8% that never experienced Imposter Syndrome are clearly psychopaths pfft